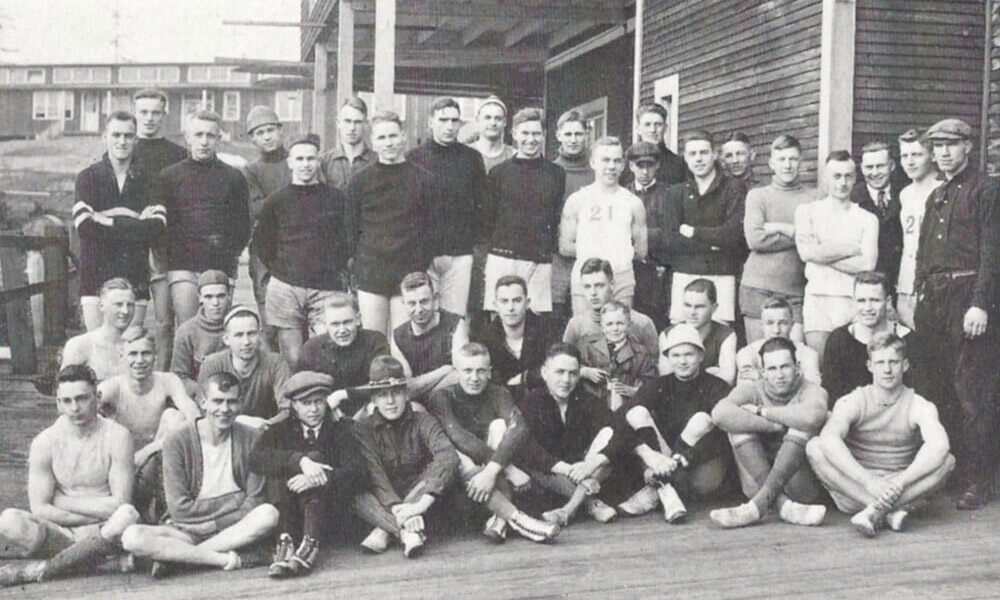

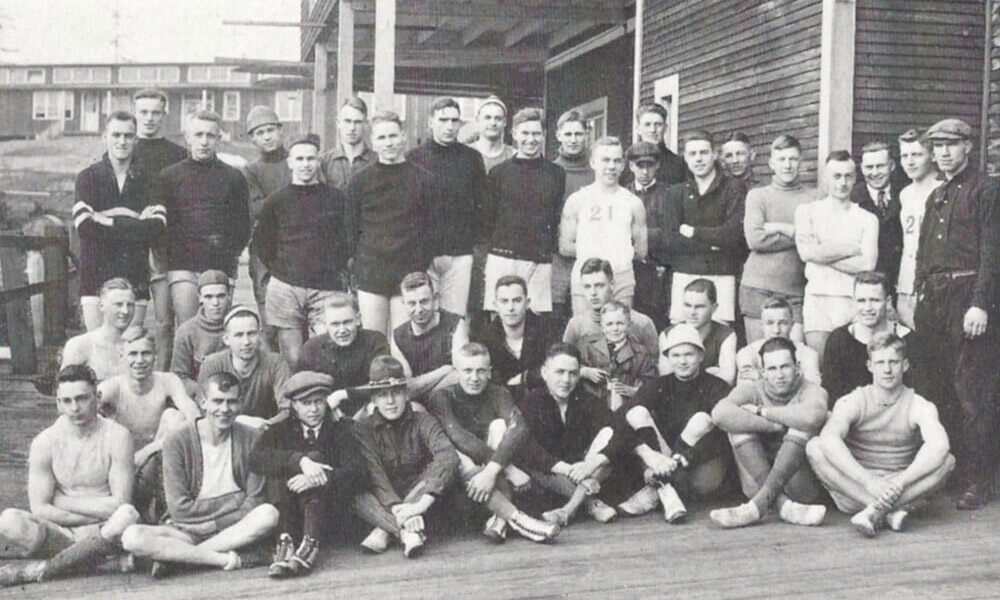

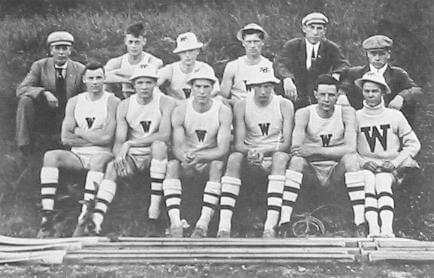

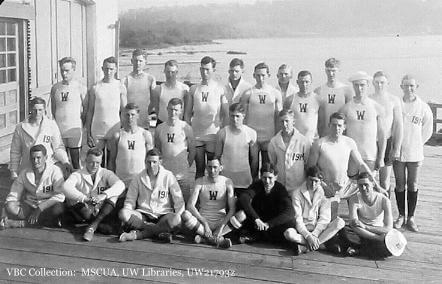

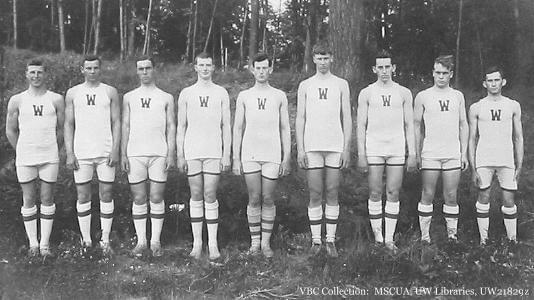

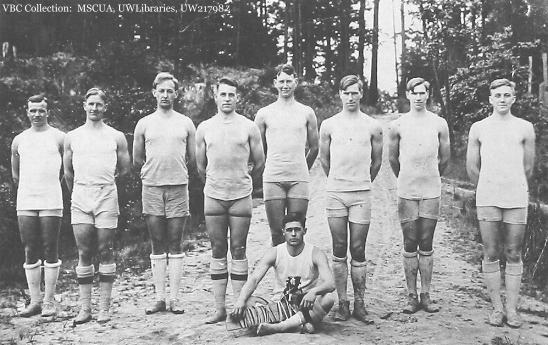

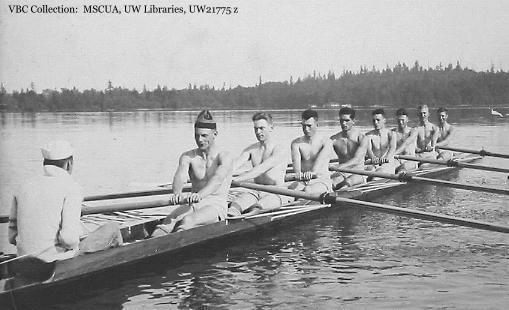

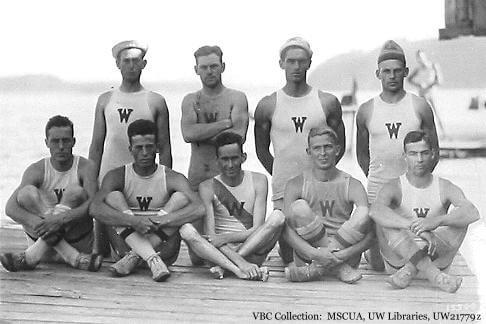

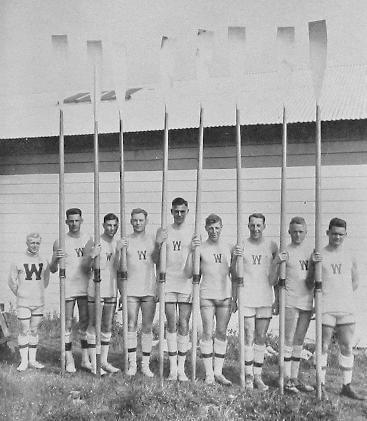

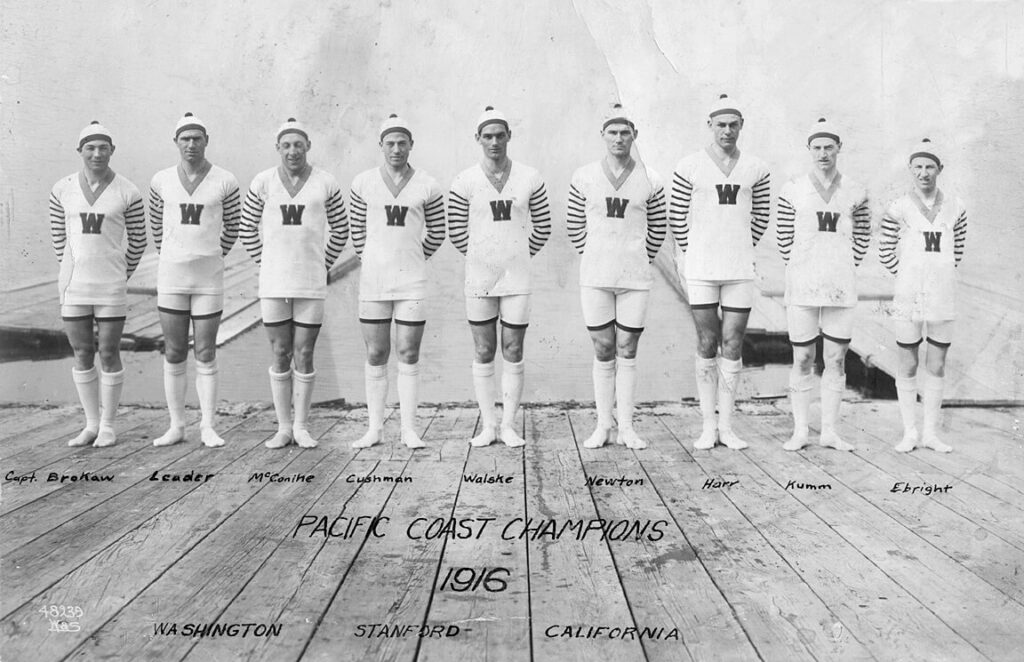

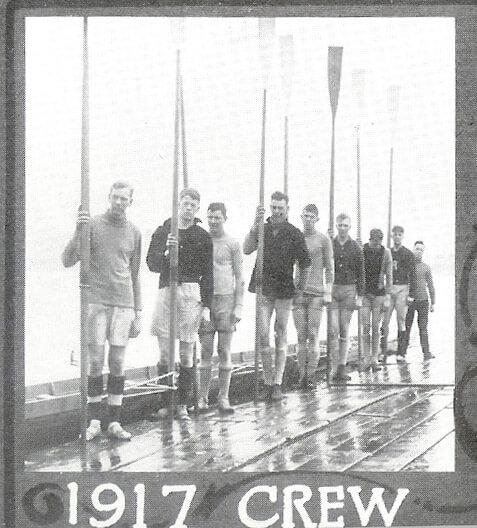

Men's Crew:

1910-1919

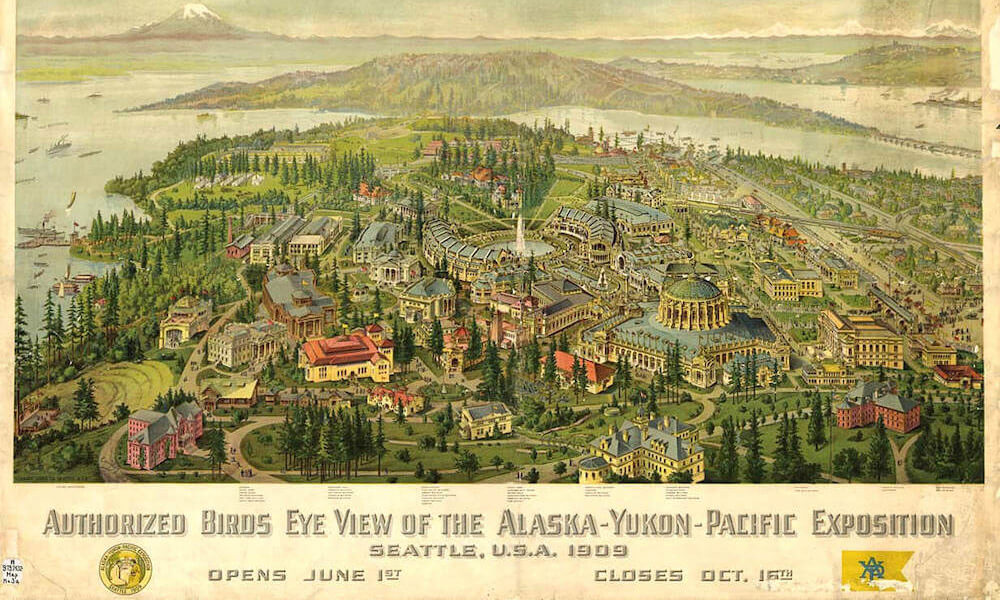

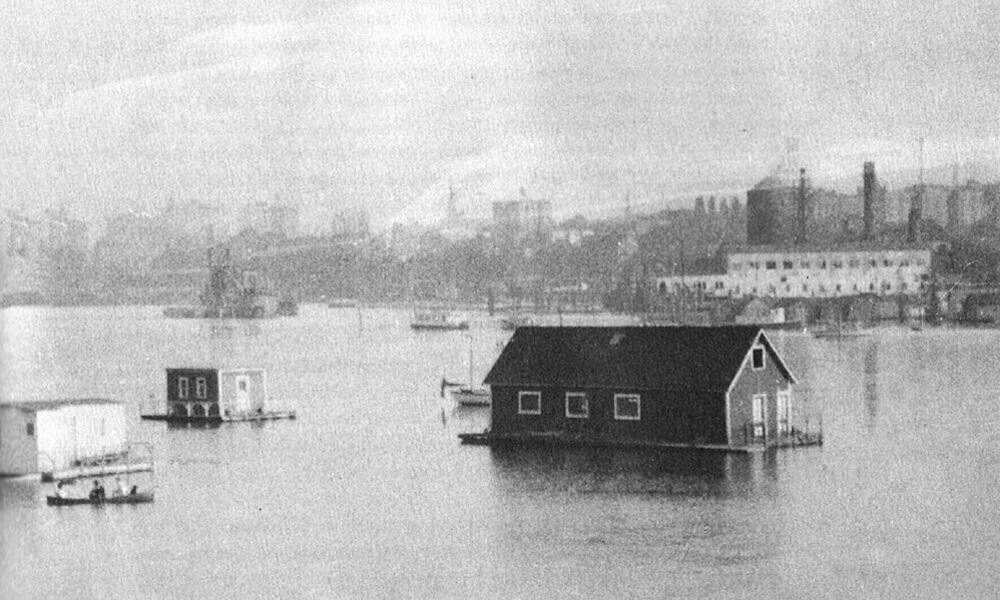

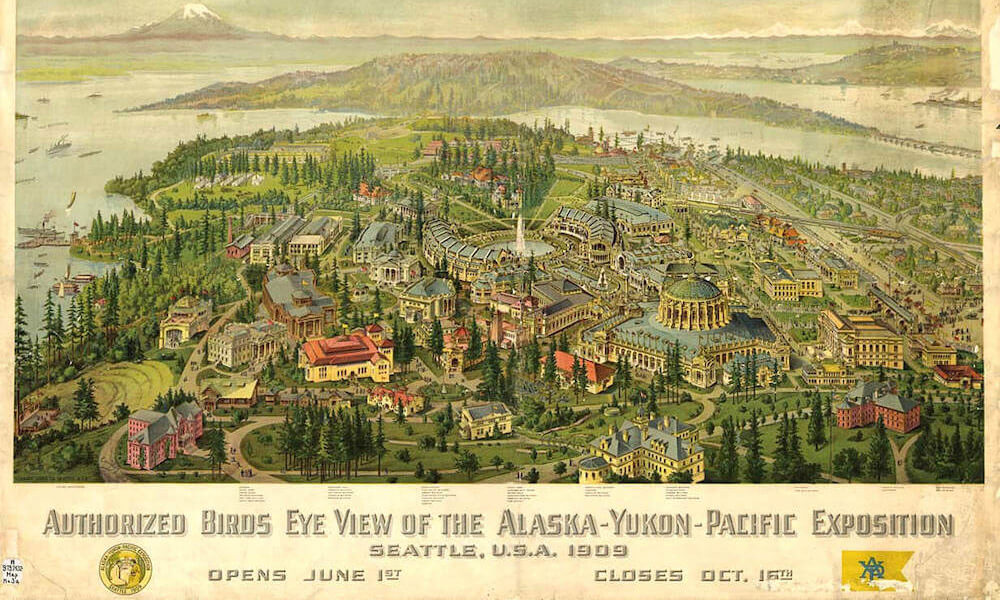

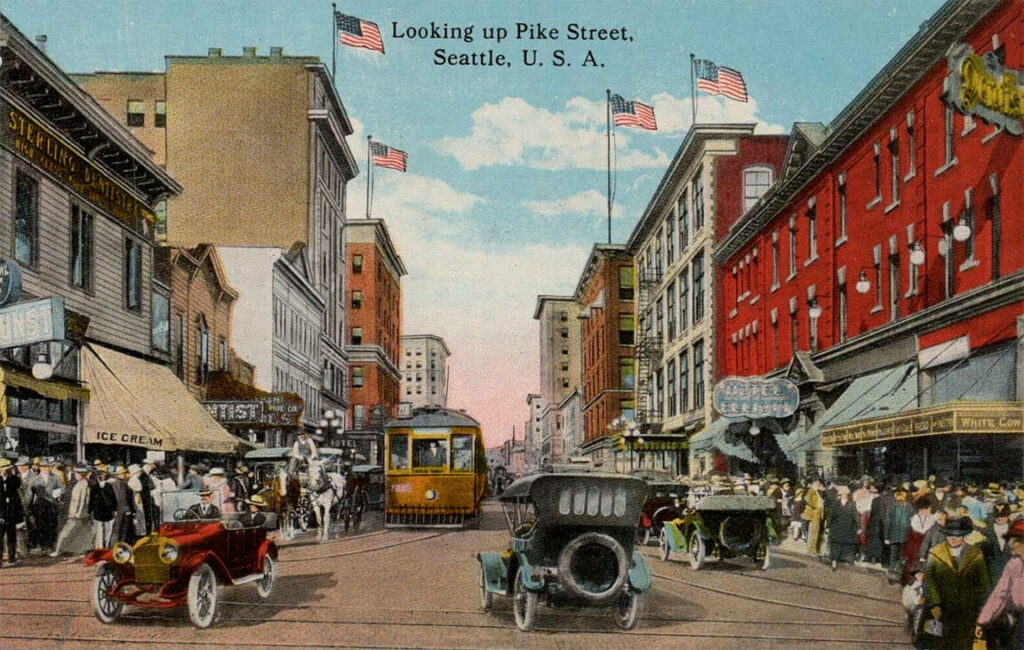

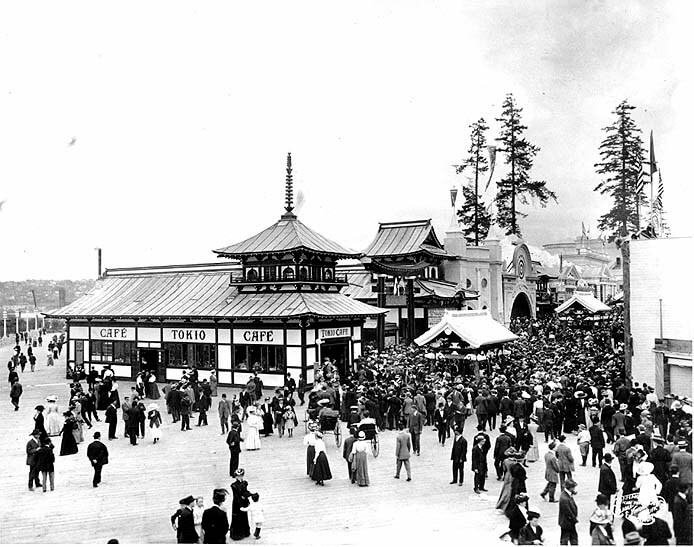

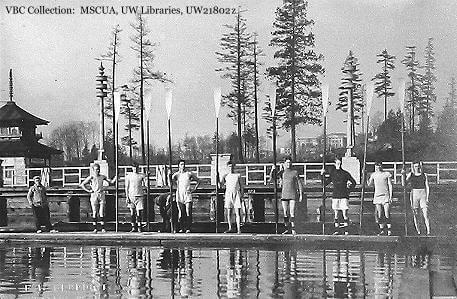

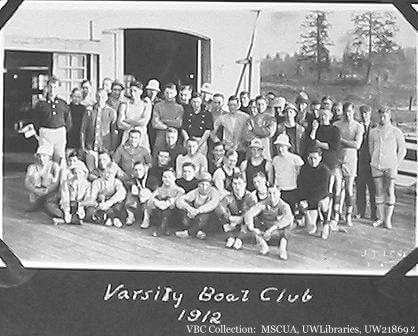

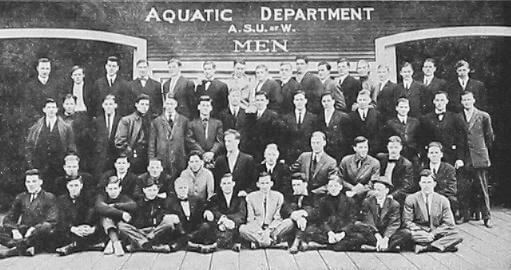

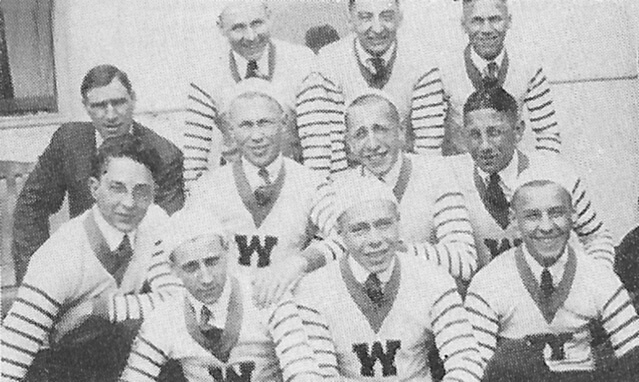

The University of Washington campus, after the Alaska/Yukon Exposition of 1909, was now physically changed, and the school was growing quickly too. Enrollment had tripled since 1905 from about 700 students to 2,200 in 1910, and more and more young men (and women) were turning out at the boathouse to find out more about crew.

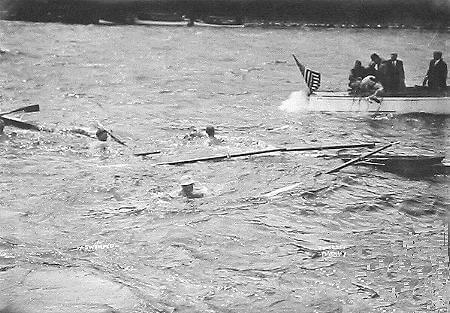

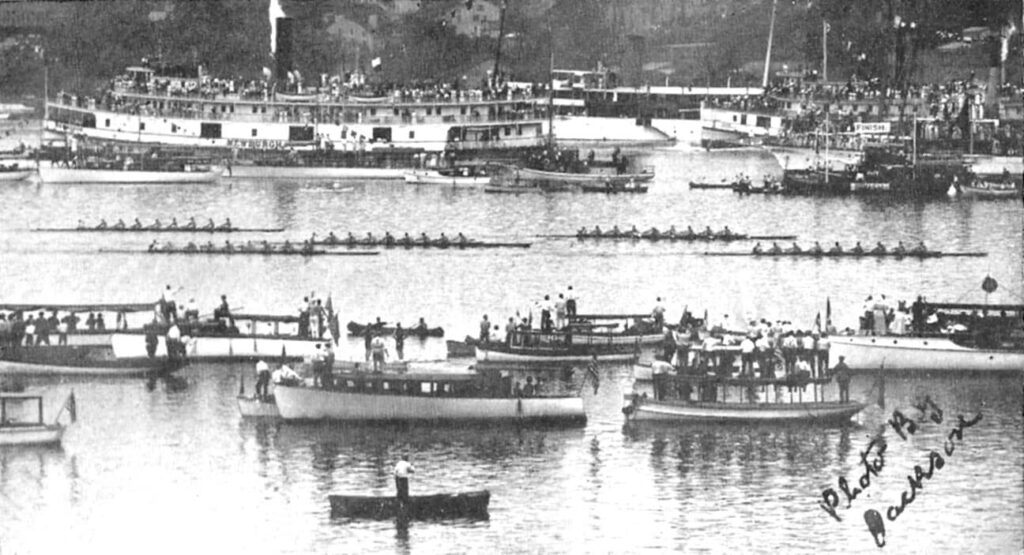

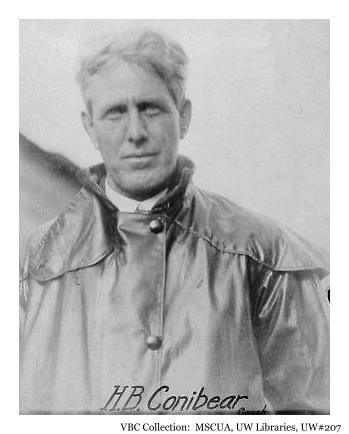

The new decade found the rowing squad at Washington firmly established and hungry for more. The coach of the program, Hiram Conibear, who had seen his hopes of a west coast dynasty dashed in 1909, now realized that to meet the goal of being the “Cornell of the Pacific” (Cornell dominated the IRA in the early century), more would be required of him, his athletes, the University, and the community.

It was in this decade that Washington Crew entered the national stage, and through that recognition brought attention to the University and Seattle itself – for some perhaps too much. For Hiram Conibear, though, the sky was the limit.