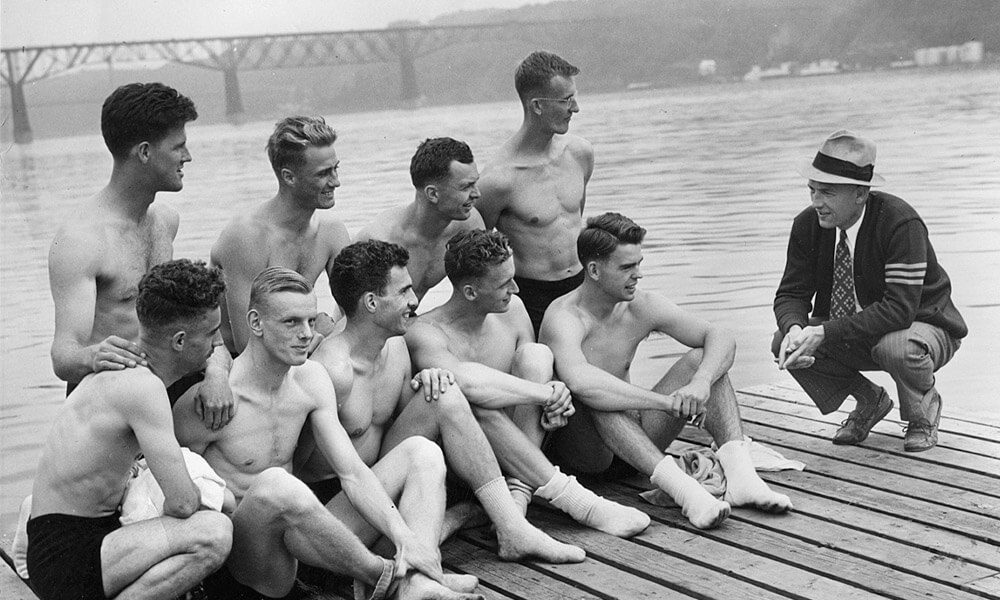

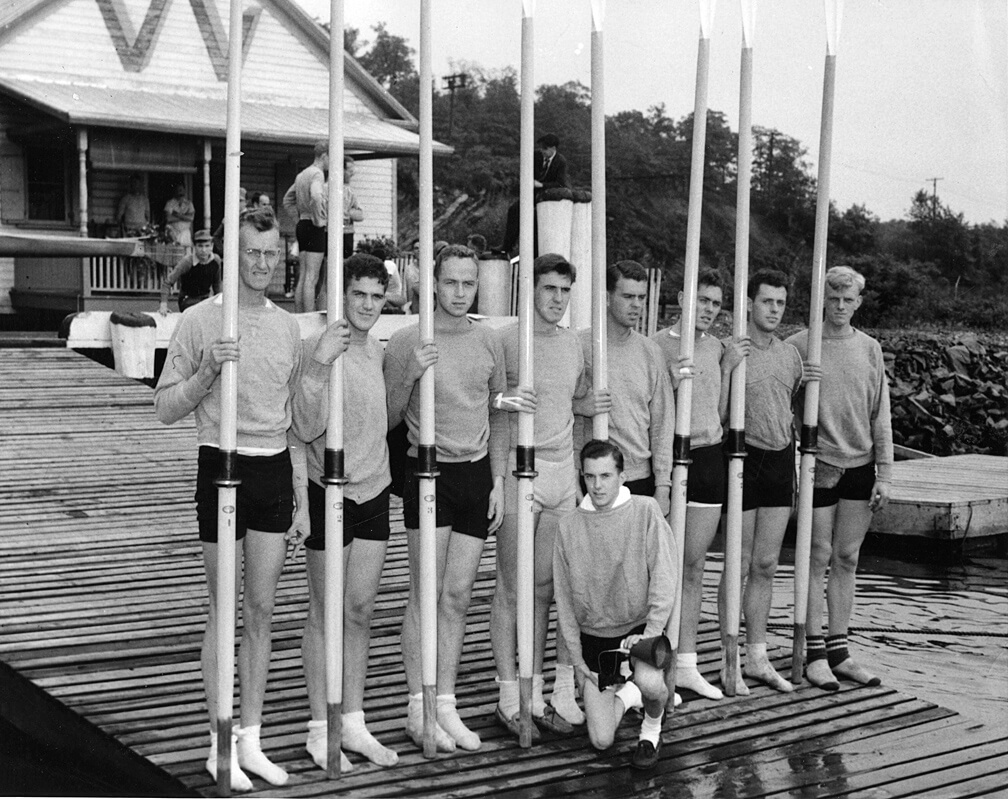

With Bud Raney leaving for Columbia, Gosta “Gus” Eriksen and Stan Pocock assumed the assistant coaching positions in the fall of 1947, Eriksen coaching the freshmen, and Pocock the lightweights. Eriksen, already a rowing legend from the thirties and previously the skiing and swimming coach at the University, had at least 200 freshmen turning out in the fall.

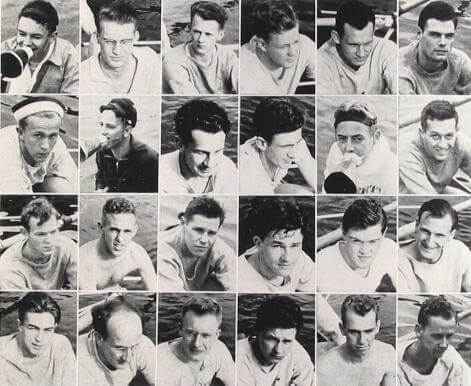

The varsity was equally as deep – young, but deep. As the winter gave way to the spring the crews became intensely competitive, an environment that Ulbrickson, over the years, had consistently fostered. Unfortunately, by the end of the year, he had a JV and Varsity crew that would not talk to each other.

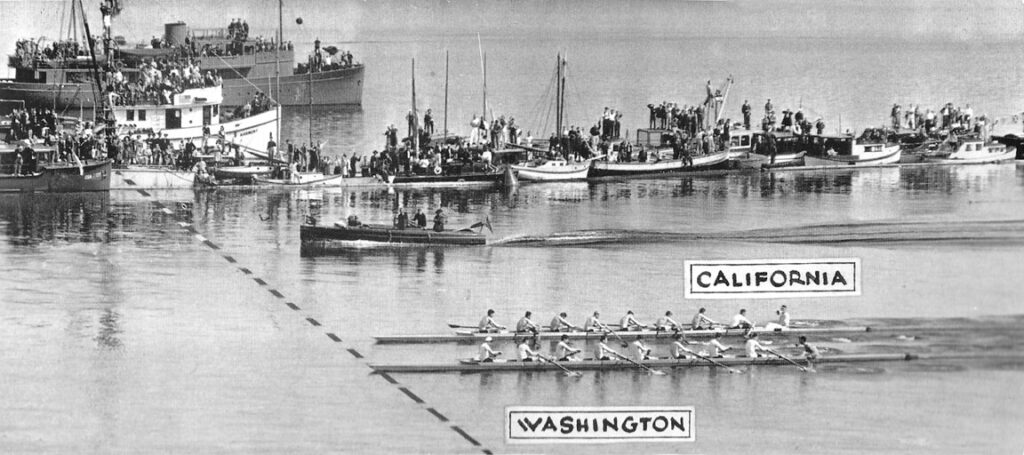

But the results on the water on May 22nd would speak volumes for the talent on this team. On the Estuary, the freshmen began the day with a two length win over the Bears; the JV’s followed up with a three length win; the varsity finished the day with a three length win. In all three races Cal took the early lead, and in the JV and Varsity events were ahead through the mile and a quarter mark, before Washington’s strength and endurance carried the crews past their competition.

About a week later on Lake Washington, the Huskies earned multiple length victories over a visiting Wisconsin JV and varsity crew. With that tune-up the men headed east for the Hudson.

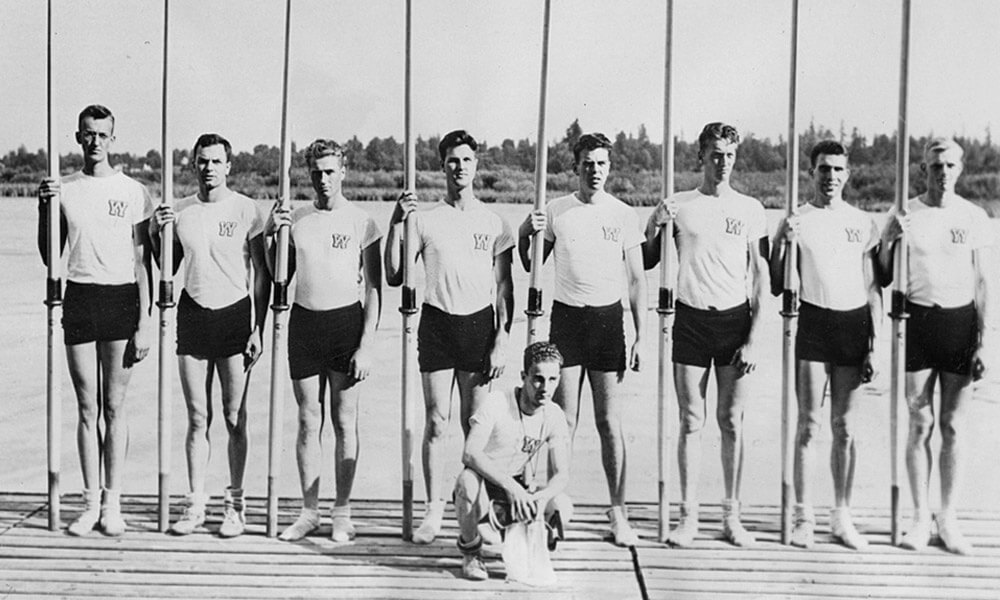

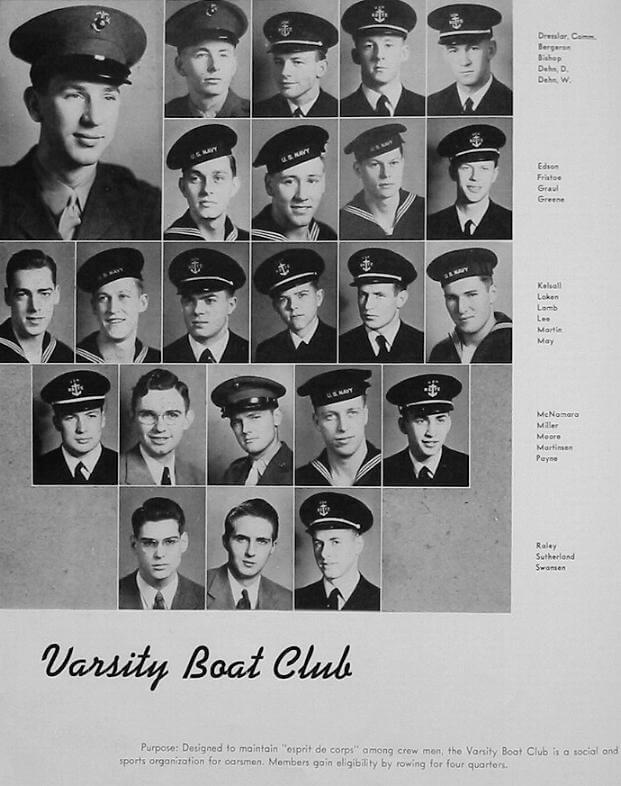

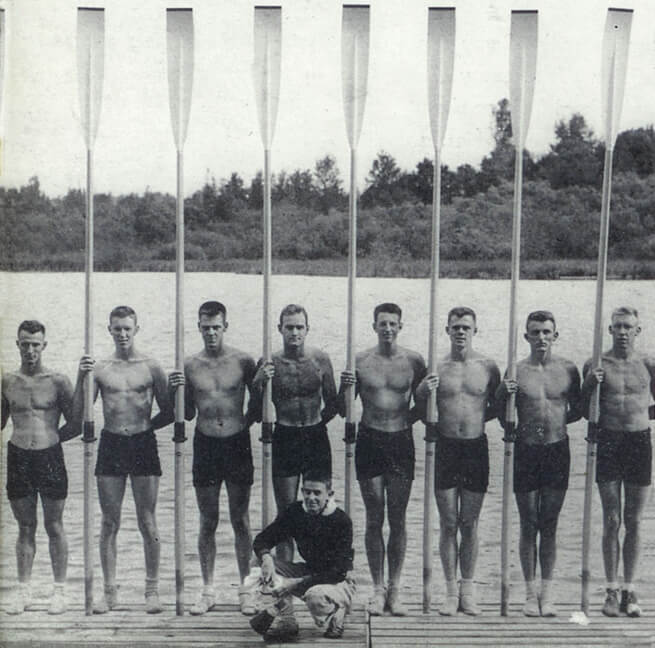

On June 22nd, the freshmen again led the charge at the IRA’s with a resounding victory in the Steward’s Cup. After a boat stopping crab in the first ten strokes, the crew settled down to overtake every other crew in the race, finally driving past the favored Navy crew to win going away by two lengths. The strong JV’s, favored to win, did so from start to finish, winning by three lengths. The varsity started well and settled to a 32, then mid-race began to move through the leaders. They passed the final crew, Navy, at two miles and finished the race in a sprint to win by two lengths, completing the third sweep for the Huskies at the IRA (the two previous were ’36 and ’37).

The next week was spent at Lake Carnegie quickly re-training for the 2000m Olympic trials. Both the varsity eight and the stern four of the JV eight went to Princeton to race, with the varsity heavily favored based on their undefeated season. In their first heat, the varsity defeated MIT and Wisconsin handily, moving to the semi-final against Cal.

On July 2nd, the varsity lined up against Cal. Cal had stayed with Washington in the first mile of each previous three-mile race, so the Huskies knew the crew had early strength. What they did not know is Cal felt convinced they could win this race based on a sub-par performance at the IRA. Cal took an early lead in the race, with Washington staying within reach, but with 500m to go Washington was behind by 3/4 length. A furious finishing sprint brought the crew back rapidly, but California won by a stunning three feet.

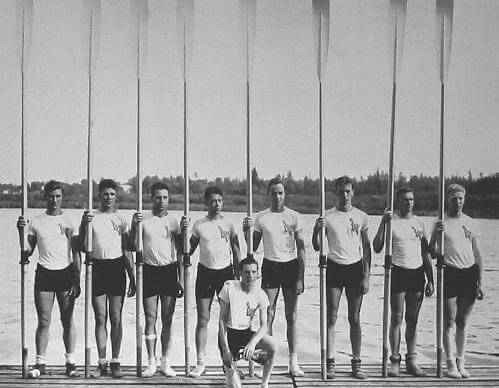

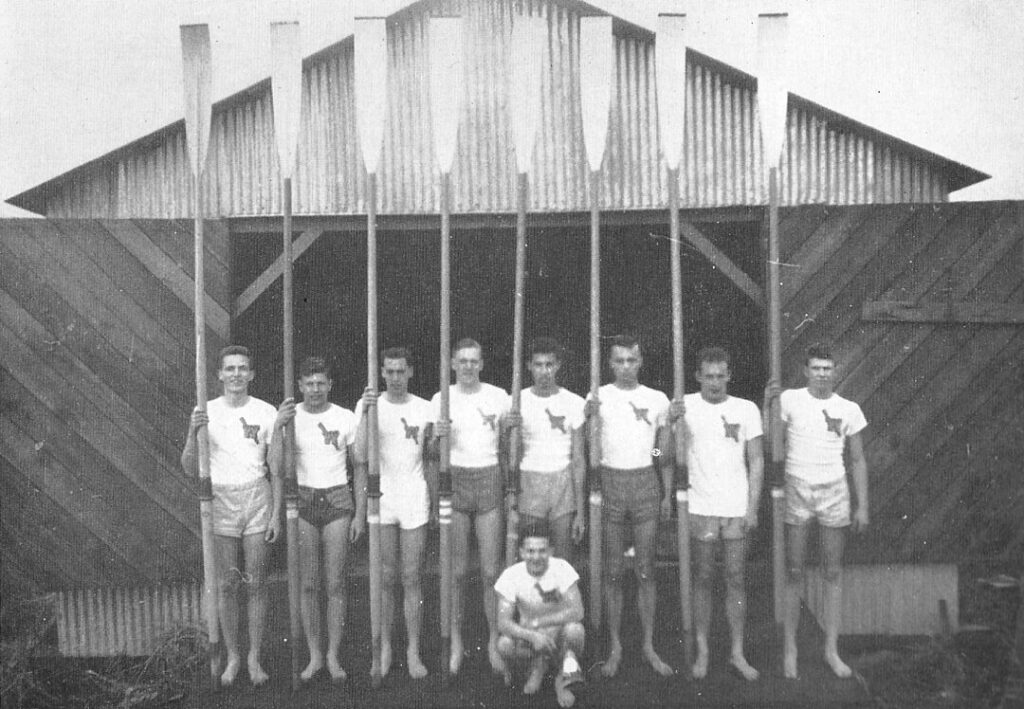

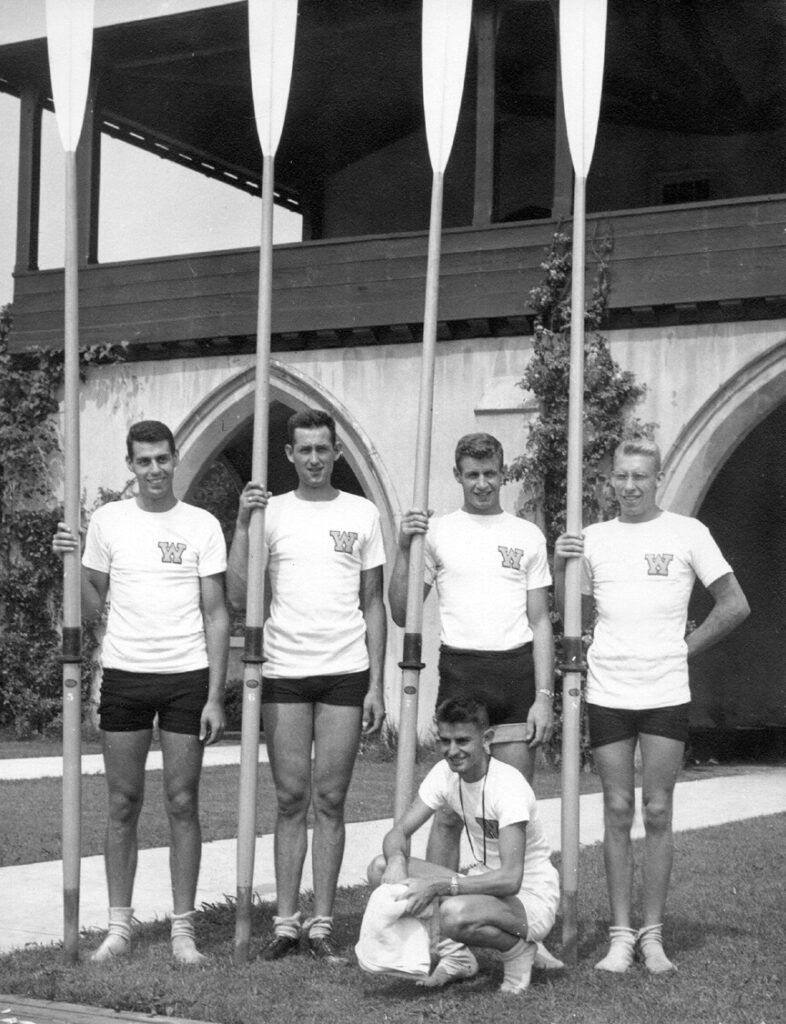

On July 10th, the Husky 4+ bested eleven other entrants at the Trials to become the U.S. representative in the fours competition. The crew sailed to London without Al Ulbrickson; he had declined the invitation to be small boats coach, ceding the job to George Pocock, who was already slated as rigger for the team. The SS America was equipped on deck with four ergometers, which the athletes shared with their new California teammates daily.

The course was at Henley. There were over 200 other crews and boats there practicing for the multiple Olympic events, and it was crowded. No launches were permitted on the course, meaning coaches on bicycles, speaking countless languages, competed for space on a three-foot wide path. Pocock, the former English sculling champion born and raised on the Thames near Eton, knew where they needed to go; eight miles down the river was a boathouse at Marlow with four miles of open water for training – and no limitations on launches. Ky Ebright did not hesitate: the two found a launch, the crews rowed the eight miles (and two locks) down the river, and there the California eight and the Washington four trained for an intense and private week as teammates.

The four began competition by defeating Finland by two lengths to advance into one of the three semis; but due to the narrowness of the Henley course, only the winner of the semis would advance to the final. In a narrow and shaky win over France that same afternoon (high stroking the first half and almost running out of gas at the finish), they won their semi to row in the medal final. Two days later, on Monday, August 9, 1948, the team lined up on the “Berks” (club) side of the river, with Switzerland to their right and Denmark a lane over from there. The men knew the other crews would jump ahead; but this time, sticking to their Pocock race plan for swing and patience (and understroking the competition), by midway through the Thames course they had pulled even with the excellent Danish squad; by 500 meters to go, the five young men from Seattle had taken the lead. In a powerful sprint – with plenty left in the tank this time around – the Husky 4+ finished two lengths ahead of second place Switzerland to win the Olympic gold, Denmark finishing third.

Later that day, California won the third Olympic gold medal of Ky Ebright’s career in the eights competition. The eight and the four were the only U.S. crews that won gold that day (the rest did not medal except the four without coxswain, which won bronze).

1948 was a watershed year for rowing at Washington. The gold medal in the four would bring on the support needed to build a new, state of the art rowing facility at Washington. The IRA sweep was a monumental achievement of Ulbrickson and his staff, and the publicity surrounding this golden year would resonate for years in Seattle.

Yet history would suggest that it was also a turning point in Ulbrickson’s career. The loss at the trials of the eight, most observers would agree, was crushing. For his highly favored and undefeated crew to lose to Ky Ebright – a man he respected as his ultimate competitor – made it worse. By three feet. The man of few words became the man of no words.

Meanwhile, the post-war economy was booming. University athletic budgets were growing. Ulbrickson, at his summer home on Orcas Island, was preparing for the next season. And although the coach would continue on for another ten years and savor the glory of victory on international waters again, 1948 remains a season that marks a turning point for the program. A new era in Washington rowing – and collegiate rowing – was beginning.