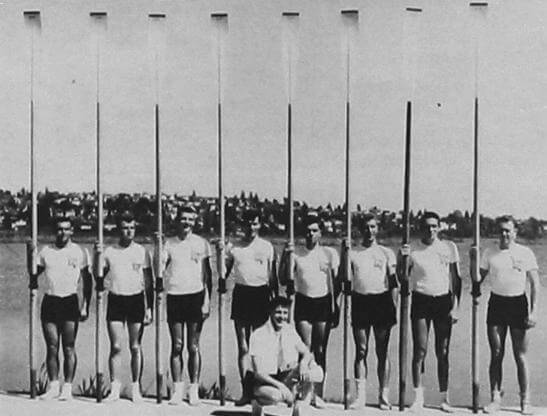

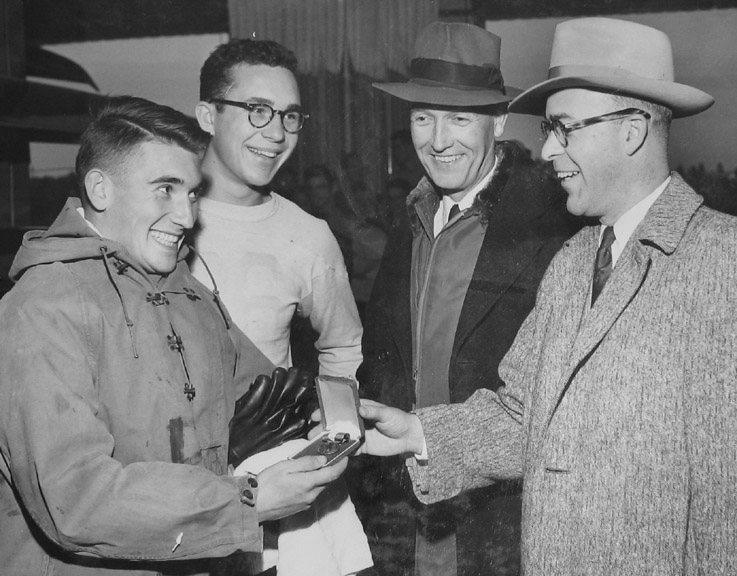

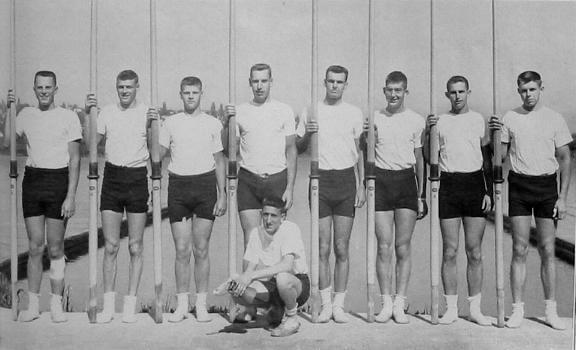

Men's Crew:

1950-1959

World War II brought global changes, collegiate athletics included. Training techniques were changing. Equipment was changing. So too were the students entering the University.

By 1950 the crew team was enjoying the first full year in a new, state of the art building – Conibear Shellhouse. George Pocock, now in his fifth decade with the team, had his own shop on site, and Al Ulbrickson had an office with a view. Hiram Conibear would have been speechless (momentarily).

But even though the complexion of rowing was rapidly changing, the fifties would be traditional in one sense: the events and results would be unpredictable. In fact, the decade served up one of the most improbable of victories, and would end with the retirement of two of the greatest legends in the sport. These events alone would thrust the program in a new direction, and would lay the groundwork for the modern age of Washington rowing.