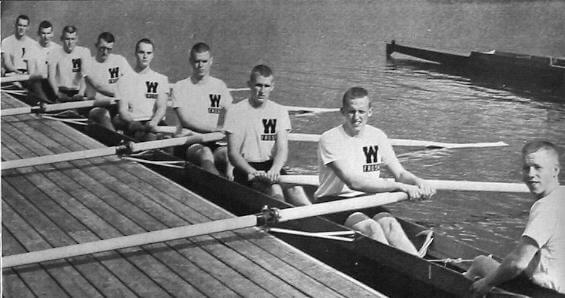

Men's Crew:

1950-1959

With the changing of the guard at both California and Washington, new faces and new training styles were set to renew the rivalry on the west coast. The sixties would include continued fierce racing at the Cal-Washington Dual, and as importantly, would also see the development of other programs throughout the west and a permanent, popular Western Sprints Regatta.

Meanwhile, rowing on the east coast was also changing, particularly with the naming of Harry Parker as coach of Harvard in 1963. The ascendancy of that program, coupled with disappointing results at the Olympics by American eights, prompted a number of training and racing changes nationally including the adoption of the 2,000 meter distance as standard at the IRA.

American culture was also evolving rapidly. By virtue of the interstate highway system, Americans were now free to travel anywhere in the car. Air travel was available. Leisure activities were no longer limited to a thirty mile radius like they had been. The television was going mainstream. And campuses across the country were becoming polarized by politics and student revolution.

Add to that the fact that sporting events were growing, both in scope and level of play. The sixties would see an explosion in professional sports and by 1967, Seattle would have their first professional sports team, the Seattle Supersonics. That same year, the first Super Bowl was played, attracting an estimated 60 million television viewers. Rowing, as a spectator sport, was on the decline; compared to Poughkeepsie, where 100,000 fans would consistently watch from shore, pack the viewing cars on the train, and line the rails of a thousand watercraft, upstate Syracuse was bringing in one-fifth as many spectators.

So put that all together, the sixties were a complicated mix of external forces and internal change that dramatically transformed the sport. At Washington, the solid tradition and community support, coupled with the continued dedication of the athletes and staff, carried the program largely unscathed into the seventies, a triumph in itself. And ultimately, out of the cloud of dust left by the upheaval of these years, would emerge a Washington coaching legend to rival any that had come before him.